An extract from The Bulli Mining Disaster 1887: Lessons from the Past by Donald P.Dingsdag.

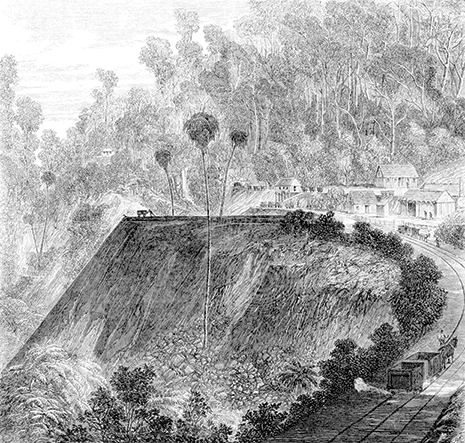

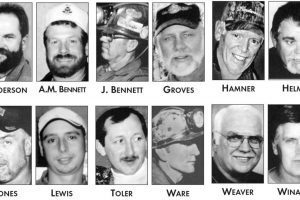

On Wednesday 23 March 1887 at 2.30 pm, an explosion occurred at the Bulli Colliery in New South Wales which resulted in the deaths of 81 men and boys. At the time numerically this was Australia’s largest coal mine disaster and today remains the second worst mine related disaster in Australian history.

The force of the explosion at Bulli, initiated by methane gas, magnified by the presence of coal dust, was restricted to a small section of the mine and killed instantly those miners who worked in close proximity to the site of the blast. Those who survived the initial force of the explosion died from the effects of asphyxiant ‘afterdamp’, a poisonous mixture of gases nearly always encountered after a coal mine explosion.

Immediately after the initial explosion several heroic rescue parties entered the mine. These men undertook this rescue task not knowing if there were any survivors or if successive explosions would cause the mine to collapse. The full horror of the tragedy began to unfold when the bodies of the miners were brought to the surface. This occurred amidst the panic and anxiety of the miners’ next-of-kin who, by that time, had assembled at the mine.

The explosion at the Bulli Mine was first investigated in NSW by a mandatory inquest which exonerated the miners and found against both the Government and the Bulli Coal Mining Company.

The Parkes Government’s response to the inquest verdict was to appoint a Royal Commission which made a report composed of commissioners who were biased in favour of the Government and the Bulli Coal Mining Company. The Government was able to arrange these favourable conditions by virtue of the powers vested in cabinet to call for Royal Commissions and to choose the Commission’s terms of reference and composition.

The Commission made recommendations regarding management and ventilation and suggested amendments to the 1876 Coal Mining Regulation Act (CMRA). However, recommendations for improved mine management were ignored. Alexander Ross, the manager of the Bulli Mine continued as manager after the explosion and the old ventilation system in place at the time of the disaster remained.

The suggestions made in order to improve the CMRA were ignored by Parliament for two years when the new CMRA was moved, only to be repressed until 1896 when it was enacted, perhaps due to the influence exercised by parliamentarians who were either coalmine owners or directors of coalmining companies. By 1890, the use of naked safety lights was universally adopted at the Bulli Mine despite the fact that it had been an open safety lamp that had caused the explosion.

Considering the immensity of the loss of life at Bulli and the potential for further disaster these were scarcely reactions calculated to make NSW coal mines safer workplaces.

THE BULLI ROYAL COMMISSION

The reasoned judgement of the Royal Commission was that the disaster occurred because a miner had used explosives carelessly. As far as the Commission was concerned, the person or  persons to blame for the accident was either ‘Westwood’ (a mine worker), or his mate (both deceased) who at the moment were working at the face of no. 2 heading and who prepared and fired the shot, which in the opinion of the Commission was the immediate or primary cause of the explosion.

persons to blame for the accident was either ‘Westwood’ (a mine worker), or his mate (both deceased) who at the moment were working at the face of no. 2 heading and who prepared and fired the shot, which in the opinion of the Commission was the immediate or primary cause of the explosion.

The indictment of Westwood and his mate ignored the actual causes of the explosion which included faulty ventilation, frequent contraventions of the CMRA, and an almost complete absence of safety procedures in the mine. One contributory factor was an oversight by Alexander Ross who, as manager and responsible person under the CMRA, neglected to ensure that his instructions regarding the firing of shots were observed.

The firing of shots created the most likely condition under which an explosion could take place, especially at Bulli where miners used highly volatile coal dust as ‘tamping’ (packing) material in the holes drilled for explosives and opened their safety lamps in a gas laden atmosphere to light the fuses. Ross had given the overman, Richard White, instructions to allow only deputies (leading hands and safety officers) to fire shots due the dangerous nature of the procedure. Yet, implausible as it seems, Ross had not provided a deputy on the nightshift. This dereliction of duty did not, however, convince the Royal Commission of any incompetence on Ross’ part in the disaster. There was no provision under the 1876 CMRA for shot-firing procedure and managers were left to use their own discretion. Ross’ inattention to shot-firing was irresponsible, not illegal. On this matter the Royal Commission commented blandly that ‘(t)he arrangement for firing shots …was unusual and unsatisfactory’.

Ross also had given instructions not to fire shots in the presence of gas, yet he had provided no means to remove such gas. He had not furnished equipment to conduct the air current to the working faces as required by the CMRA. Nevertheless, he was only guilty of a small oversight, and according to the Royal Commission:

“… the deputy Robert Millward [sic] deceased, Richard White, overman, and to a less extent (except in the matter of providing bratticing for which he was alone responsible) Alexander Ross, manager, were guilty of contributory negligence.”

This was one of the few instances in which Ross was reprimanded in the Commission’s lengthy summation.

There were several ventilation problems at the Bulli mine. One of the more serious was the use of a system which brought gas from one ‘heading’ (tunnel) to other headings. Another problem was the failure to ‘brattice’ (construct, a ventilation partition made from planks and/ or cloth) up to the face. The accumulation of gas as a result of the ventilation system introduced by Ross, and approved by Messrs Rowan and Mackenzie (government mine inspectors), did in all probability cause the explosion. The Royal Commission, however, merely believed that ‘it betrayed an absence of forethought’ by Ross.

The air current at Bulli was drawn in at the ‘adit’ (entrance/ drift to the mine) and after being prevented from entering several unused workings and tunnels by ‘stoppings’, walls made from worthless pit-stone, the air was divided into two main portions. One portion supplied the Western district, the other the main tunnel to the Hill End district where the explosion took place. The dividing of the air at the junction of these tunnels was brought about by a door with a regulating shutter which directed the amount of air that passed to each district. The air in the main tunnel was then conducted through the No. 1 heading into the No. 2 heading via a ‘cut-through’. According to the CMRA, as headings advanced they had to be connected every 35 yards by cut-throughs or ‘stentons’ in order to allow the air to circulate near the advancing coal face which was the most likely location for gas. To prevent air from escaping through old stentons, these routes were sealed with stoppings as the headings progressed.

After passing through No. 2 heading from No. 1, the air was then circulated to headings 3, 4, 5 and 6, which were also driven off the main tunnel. In order to prevent the air from going straight up the main tunnel, a door was placed between Nos. 1 and 2 and each subsequent pair of headings. Every heading had working places or ‘bords’ (where the coal was cut from the ‘face’) driven off them to each side. As each bord was ‘worked out’ of coal it was also partially sealed off by loosely stacked porous pit-stone stoppings to minimise the air current circulating through. This cost-cutting device, although not illegal, was another doubtful mining practice as unused bords were precisely the locations where ‘firedamp’ (methane) might accumulate. As the ’working’ bords advanced, they too were supposed to be connected with cut-throughs if their length exceeded 35 yards.

The shortcomings of the ventilation system used at Bulli were numerous. When gas was encountered in the No. 1 heading and some of its working bords, it was conducted into the No. 2 and successive heading to be emitted by the ‘furnace’, an underground fire which expelled the air by convection through a vertical shaft to the mine’s surface. The direction of the air current swept explosive firedamp into sections where men were working with naked lights. The regulating door at the junction of the main tunnel and the Western tunnel as well as the doors between the headings were frequently opened, allowing for even a greater accumulation of gas.

The installation of a new furnace, which had trebled the volume of air, had lulled Ross and the overman, White, into a false sense of security. It appears that Ross and White had neither the expertise nor cared to ensure whether or not the air supply reached the critical destinations, the working faces in the headings and bords.

Although Ross’s ventilation system was criticised by some of the witnesses kindly disposed towards him, the members of the Royal Commission did not feel disposed to attach any blame to Ross, and conceded that Ross had depended too much on the improved air current and admonished him for not using bratticing.

During the sitting of the Royal Commission, a frequent criticism of the Bulli ventilation system was that double doors were not generally in use in the mine. Yet, no mention of double doors was made at the preceding inquest by the same witnesses, until a Bulli miner, John Hobbs, reminded them that it was common to use double doors in Britain. The single door system used at Bulli frequently caused the derangement of the air current and aggravated the build-up of gas. Because the doors had been placed thoughtlessly in the air tunnels which were also the main traffic thoroughfares, the doors had to be frequently opened to let up to twenty ‘skips’ (small coal wagons on rails) past. The ventilation of No. 1 and No. 2 headings was entirely dependent on two single doors. In fact, the entire district and the life of every workman in the district was also dependent on those two single doors.

Ross did not feel that double doors were a necessity; neither did the Commissioners, who believed that:

“(i)n the case of Bulli, the lengths of trains would have necessitated their being placed 160 feet apart. This under the circumstances would have been impossible and the practice is not pursued in any Australian colliery.”

“Miners were used to smoking in the ‘gassy district’ and were permitted to carry tobacco and matches underground.”

“Mr Alexander Ross, the manager of the Bulli Mine, continued as manager after the explosion and the old ventilation system in place at the time of the disaster remained.”

The circumstances which prevented the use of double doors were financial considerations only. This was typical of the parsimony which prevailed in the industry during the nineteenth century; partially owing to the intermittency of trade, but also as a result of a traditional antipathy to investment on equipment that was not considered necessary. There were no practical obstacles for excluding the doors as Ross and the Commissioners suggested.

During the course of the Royal Commission, there were numerous references made by Dr James Robertson, the presiding commissoner, mining engineer and coalmine owner, individual miners and managers in relation to the high safety standards in Britain, yet these standards were not implemented in NSW. It would appear that the unquestioning acceptance of inadequate safety measures in NSW in general and by all concerned with the Bulli mine had led to the explosion.

The driving of headings and bords more than 35 yards ahead of the air was another gross transgression of the CMRA, Generally, this widespread malpractice was also motivated by cutting costs and served to compound the problems associated with the ventilation system at Bulli. As headings and bords were advanced they often came upon the problem of the dykes (igneous stone intruding into the coal) and rolls, which meant that production was hampered by the mining of worthless stone. A financial hurdle arose when the next stenton to the adjoining heading or bord had to be cut through this waste material.

To avoid this costly exercise, managers often ignored the CMRA 35 yard regulation. They cut stentons only where coal was known to exist. On occasions at Bulli, cut-throughs in bords and headings were more than 42 yards ahead of the air. This illegal practice was condoned by both Rowan and Mackenzie. On that breach of the CMRA alone, Ross should have been charged by Rowan who was supposed to check the distances between cut-throughs. Instead of inspecting the entire colliery once every eight weeks as stipulated by the CMRA, Rowan had aggravated the ventilation and gas problem by not inspecting the mine regularly. The Commissioners recorded:

“(e)xcepting Nos. 1 and 2 headings the Commission are inclined to accept the testimony of the only trustworthy authority that submitted themselves for examination – Mr Inspector Rowan who, although his visits were frequent, yet found no amount of gas in this section, and the minute examination of the colliery by the Commission confirms this.”

The exception to evidence given by Rowan pertaining to heading Nos. 1 and 2 was probably a measure to safeguard Rowan’s integrity because he had claimed while giving evidence that he had never detected any gas. Contradictory to Rowan’s evidence, the source of the explosion had been heading No. 1 or No. 2, which confirmed the report by miners of gas in the area – this report incriminated Rowan.

The overturning of the miners’ evidence increased as the controversy over the quantities of gas escalated. While having been mildly censured for not making regular inspections of the pit, Ross, like Rowan, was elevated in status as an expert witness. In particular, his evidence regarding the quantity of gas was considered to be reliable. The Royal Commission recorded that:

“(t)he evidence of the Manager, Mr. Ross, who did not often inspect the workings, and of his overman, Richard White, points to the presence of small quantities of gas only.”

The reference to Ross’s infrequent inspections is phrased in an euphemistic fashion. Ross seemed to possess only a poor knowledge of the underground workings. After the explosion, while leading a search party, he was forced to concede that he had lost his way. Obviously, Ross lost his way because of the infrequent number of inspections he had made of the mine. Accordingly, his knowledge of gas problems in different parts of the mine must be suspect.

Several experienced miners who had worked in headings No. 1 and 2 had reported large quantities of gas before and after the strike, and gave evidence accordingly. One drillhole in the face of the No. 1 heading emitted so much gas that it could be heard to ‘hum’ some 40 yards away. While this volume of gas was not dangerous, it suggested the presence of firedamp which the Royal Commission was so intent on denying. The Commission refuted the miners’ claims, recording that:

“(t)his starting [sic] statement emanated from men who had no extensive knowledge of mining or any previous experience of firedamp”;

and:

“(i)n other respects the statements of these witnesses were not borne out by those of calmer more intelligent and truthful men.”

Those calmer, more intelligent and truthful men were the miners whose evidence had supported the evidence of management and Department of Mines’ officers.

When the deputy, James Crawford, was shown the hummer – an audible issue of gas, he inserted a gas pipe with a tap into the drillhole to convince Ross and White of the large quantities of firedamp. The purpose of the tap was to allow the gas to escape only when it was turned on. In the presence of Ross and White, the gas was lit by Crawford, irresponsibly with a naked light. The force of the gas was so strong that it extinguished the flame if the tap was turned on more than half way.

The above act of bravado demonstrates the small regard miners had even toward their own safety. Under examination by Robertson, Ross played down the size of the blower. He claimed that Crawford had inserted the pipe in the hole to show his ingenuity. The Commission readily accepted Ross’s explanation, recording that there was:

… evidence of a small blower in No. 1 heading from whence gas issued for some weeks into which a pipe was fixed. It, however appears to have issued with no great force.

Ross, nevertheless, with justification protested to the Commission about Crawford’s use of a naked light under such dangerous circumstances. Ironically, Ross’ protestation about Crawford’s use of a naked light in a gas laden atmosphere corroborated the miners’ evidence concerning gas. The company had also implicitly acknowledged the existence of firedamp by distributing safety lamps. Safety lamps had to be issued once firedamp was encountered in accordance with the Special Rules (local rules made under the CMRA to suit the risk context of individual mines).

The purpose of the Davy safety lamp was twofold. It was used by deputies to detect gas, as firedamp is undetectable by human senses, being tasteless, odourless and colourless. Even today, similar principles apply to the detection of gas. The size and colour of the flame determines the volume and constitution of the gas. If the volume of gas is greater than the volume of air, the flame will extinguish automatically. The second use of the safety lamp is as its name implies. The flame is enclosed by two separate gauzes and a glass case. Air can enter the lamp, but the flame cannot escape and ignite the gas outside the lamp.

Ross’s failure to ensure that safety lamps were locked, cleaned and fitted with gauzes was not deemed punishable by the Commission. Once the existence of gas was established, safety lamps had to be circulated to miners in the affected section. The CMRA specified:

“(w)henever any safety lamp is required to be used it shall be first examined and securely locked by some person duly authorized for that purpose who shall keep the key thereof.

Those regulations were not adhered to by either the overman, or the deputies. Ross did not ensure that his instructions concerning the locking of safety lamps were observed. From the Commissioners’ point of view:

“Mr Ross issued instructions to his overman and deputies to lock all lamps; but that for some cause, and unknown to Mr Ross, this order had not been strictly carried out for some weeks preceding the explosion. At the same time the Commission are fully aware how very difficult it is to get subordinates to carry out orders in their integrity .”

The issue of safety lamps was an unpopular one with miners because they gave off a very dim, flickering, orange coloured light. In general, miners preferred to work with the brighter naked light and were determined to make use of this method of lighting even if safety regulations were flouted in the process. While the safety lamps were easily extinguished by even a slight disturbance, they were very hard to light again if they were locked. The illumination of miners’ immediate working quarters was entirely dependent on two dim safety lights. Miners at Bulli and elsewhere typically worked on piecerates in teams of two were anxious about lost time if their light was accidently extinguished.

An extinguished light often resulted in a long walk by one of the team to the deputy’s cabin in order to have the lamp lit as all lights were kept under lock and key by Crawford. This time consuming process was considered an annoyance by the men and whenever possible, the miners tried to avoid working with locked lights despite the obvious dangers associated with this procedure.

The management at Bulli rarely enforced strict discipline and the men responded accordingly. Miners were used to smoking in the ‘gassy district’ and were permitted to carry tobacco and matches underground.

While the Special Rules provided that a danger-board be erected across the entrance of any section where firedamp was found, this procedure was not always strictly followed. In the No. 1 heading where sizeable amounts of gas issued, a danger-board was hung at the last stenton. Nevertheless, the miners continued to smoke carelessly just outside the danger-board.

The night before the explosion Thomas Morgan, a ‘wheeler’ (a worker who pushed the skips by hand in the bord and led the horse-drawn skips in the tunnel), had hung his naked light on the danger-board after he was requested to do so by William Hope, an experienced miner. Notwithstanding that his light was 28 yards from the face, the action ignited firedamp with a sheet of flame more than 4 yards long. As no official was present during the incident, neither Hope, Morgan, nor any of the men working that shift bothered to report the incident to White the overman, or to any other official. The men had become so accustomed to the elements of danger and so familiar with working under life threatening conditions that after their shift they did not consider it necessary to call at White’s house which was near the pit to report the sudden eruption of gas.

Another motivation on the part of the men for not reporting the incident to White was fear. It was generally believed by Bulli miners that they would lose their job if they reported any danger.

The reason miners gave for not reporting particular hazards was the belief that the ‘Engagement Rules of the Bulli Colliery’ precluded them from reporting anything to the manager or Department of Mines inspector. The section which miners misinterpreted was rule No. 6 which decreed that:

“(a)ny employee interfering in any way with the orders issued by the colliery manager or his overman for regulating the work of the mine shall be liable to dismissal without notice.”

Rule No. 6 was preceded by Rule No. 5 which stated that:

“(t)he colliery manager shall have full command over all employees in or about this colliery. They shall apply to, and take their orders and instructions from him or such other person as may be appointed to act on his behalf.”

Notwithstanding the miners’ misinterpretations of Rules No. 5 and 6, one candid reason why they could not report the dangerous situation was the fact that according to Rule No. 3 of the Engagement Rules, miners could not leave their allotted working place. Rule No. 3 stated that:

“(a)ny miner or other employee found in any part of the mine or colliery other than that in which he should be working without the consent of the colliery manager, shall be liable to dismissal without notice.”

An extract from The Bulli Mining Disaster 1887: Lessons from the Past by Donald P. Dingsdag. First published in paperback by St Louis Press, 1993 copyright 1993 Donald P. Dingsdag

| PROFILE Dr Don DingsdagDr Don Dingsdag is a senior lecturer/ consultant in OHS, risk assessment, safety management, safety culture and safety leadership in the School of Science and Health, University of Western Sydney. He has approximately 110 publications, including nine reports, three books in OHS; five book chapters (refereed and one in German) in OHS, 50 refereed articles and refereed conference proceedings including 17 in international publications; of these more than 20 are in OHS/ safety management/ safety culture/ safety leadership. He has completed 15 competitive grants in safety management, safety culture and safety leadership totalling more than $2.2 million. |

Add Comment