The shocking fall and subsequent deaths of two maintenance workers at the Mt Lyell Copper Mine in Tasmania, made everyone in the safety industry catch their breath. In this article, we examine a case study in fall arrest and provides strategies for minimising falls at mines.

In our highly regulated resources sector, how could an accident of this kind of fall down a mine shaft – still happen? Was it human error, equipment failure, lack of training, poor supervision, bad safety systems or a combination of all of the above?

At the time of writing, investigations into the accident were still underway, however for some, the entire incident brought back memories of the horrific incident in 2012 that saw a rigger fall down a 14-metre mine shaft due to a series of broad-ranging safety breaches.

The accident at Perilya mine in NSW makes a fascinating case study for any mine safety professional and reminds us all why the rules are there.

The following case study is an extract of the Investigation Report prepared by the NSW Mine Safety Investigation Unit, 23 May 2014.

An investigation into the serious injury of a mine worker at the Perilya Broken Hill Southern Operations Mine, Broken Hill, NSW on 8 June 2012.

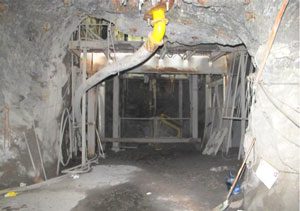

At 9.47 am on 8 June 2012, a 51-year-old rigger was seriously injured when he fell from an elevated loader bucket of a Caterpillar front end loader at the Perilya Broken Hill Southern Operations Mine. The incident occurred about 1140 metres underground at the southern ore weighing and loading flask (weigh flask) on the 26 sub-level of the NBHC Haulage Shaft.

The rigger was using the loader bucket as an elevated work platform and it was suspended over the shaft. While attempting to secure a large weight to the weigh flask, the rigger fell about 14 metres to the base of the shaft. There was a second worker in the loader bucket at the time of the incident. The second worker was not injured.

An unrestrained steel weight basket containing three weight blocks (combined weight of 9.8 tonnes) also fell from the loader bucket and became lodged on steelwork in the shaft. One of the weight blocks, weighing 3 tonnes fell from the basket to the base of the shaft.

The rigger’s fall arrest system did not arrest his fall.1

The rigger’s right leg was severed during the fall. He also suffered three spinal fractures, seven broken ribs and a lacerated liver.

The rigger was rescued by mines rescue personnel, evacuated from the mine and provided emergency medical treatment.

Investigation observations

- The investigation identified a range of factors that contributed to the incident, summarised below:

- Fit-for-purpose equipment

- The loader bucket was not designed to be used as an elevated work platform.

- The loader bucket was not designed to be used for the purpose of lifting steel weight baskets or people.

- The fall arrest system used did not restrain the rigger’s fall.

- There was no energy absorbing device incorporated in the rigger’s fall arrest system.

- The method that the rigger used to connect the lanyard to the loader bucket was not recommended in the published guidelines in AS/NZS 1891.4:2009.

- The fall arrest system equipment that the two mine workers used had not been stored and inspected under the mine’s fall arrest equipment storage and inspection system.

- Several components of the fall arrest equipment that the two mine workers used would not have passed a ‘fit for purpose’ inspection.

- The loader bucket was not designed to be used as an elevated work platform.

- The loader bucket was not designed to be used for the purpose of lifting steel weight baskets or people.

- The fall arrest system used did not restrain the rigger’s fall.

- There was no energy absorbing device incorporated in the rigger’s fall arrest system.

- The method that the rigger used to connect the lanyard to the loader bucket was not recommended in the published guidelines in AS/NZS 1891.4:2009.

- The fall arrest system equipment that the two mine workers used had not been stored and inspected under the mine’s fall arrest equipment storage and inspection system.

- Several components of the fall arrest equipment that the two mine workers used would not have passed a ‘fit for purpose’ inspection.

READ RELATED

- The height of safety

- How do you plead? Guilty for failing to discharge safety & health obligation

- Come along incident results in huge fines

Competent people

- Supervisors involved in the task planning did not document how the task was to be performed.

- Task assessment documentation created by the rigger was inadequate and was not reviewed by the supervisors who had planned the task.

- There was no supervisory oversight of the task being undertaken.

- The rigger held certificates of competency as a Dogman (Class 2) and Rigger (Class 1). The rigger’s working at heights competencies were obtained following a one-day training course completed in 2007 and recognition of prior learning in 2011.

Safe work practices

- This was the first time the mineworkers had undertaken the task.

- The system of work envisaged by mine supervisors was not the system of work used by the mine workers to undertake the task.

- The task documentation created by mine supervisors did not specifically identify how the work task was to be performed.

- Verbal discussions had taken place between supervisors and the rigger before the incident but safe work procedures were not documented.

- The mine did not permit the use of the loader bucket as an elevated work platform. However, this prohibition was not specifically documented in mine procedures.

Foreseeable risk

Figure 8: Incident simulation conducted on 28 June 2012 showing the approximate positions where the two mine workers were standing in relation to the untethered weight basket in the loader bucket.16 Note: The two mine workers were both wearing full body harnesses individually attached by a rope lanyard back hooked to the top of the bucket. The synthetic fibre slings around the base of the weight basket at the time of the incident are not shown in this simulation.

The mine had documented risk assessments in place that identified the foreseeable risk of people falling down a shaft when conducting tasks in and around shafts. To control the identified risk of falling down a shaft, fit-for-purpose fall arrest equipment was required to be worn for various tasks undertaken in and around the shaft.

According to the mine, the use of a loader bucket as an elevated work platform was prohibited at the mine. However, this prohibition was not specifically documented in any of the mine’s safety management plan records or training documents.

Fall arrest safety equipment – harness and lanyard

Both mineworkers at the time of the incident were wearing full-body harness fall arrest equipment (see Figure 15).

Both mine workers also used a similar 2 metre rope lanyard attached from the rear dorsal of the harness back secured to the top of the loader bucket.23

Neither mine worker used a personal energy absorber (deceleration device,24 inertia reel,25 karabiner26) attachment to the lanyard at the time of the incident.

Investigators engaged height safety consultants to inspect the fall arrest equipment to provide an assessment of the condition of the equipment (see Figure 17).27

An extract from the consultant’s report dated 4 October 2012 made the following observations about the rigger’s damaged lanyard end:

The three-strand 12mm diameter (measured 14.7mm diameter due to grit and moisture content) rope has been broken. The breaks in the strands occurred at different distances from the splice. The ends show signs of failing under load.

Some fibre ends on strand ‘C’ are ‘balled’ indicating melting – fail.

No sharp cuts are visible at the failure site. The spliced eye of the rope shows significant wear and grit build up – fail.

The lanyard is four years old and extensively worn and so is unlikely to have had the required strength of 15kN.

The lanyard was connected to the loader bucket by means of reeving. The reeving would have reduced the lanyard’s strength by between 25 and 60% (i.e. 11kN to 9kN)

The length of the lanyard was such that it allowed (the rigger) to fall out of the loader bucket and therefore into a fall arrest situation. The lanyard (the rigger) was using was a restraint lanyard. It had no energy absorber and consequently, it was not the correct lanyard for the task where a risk of a fall existed.

All lanyards except pole straps are required to have energy absorbers incorporated in them if they are to conform with AS/NZS 1891.1:2007 Part 1 Harness and ancillary equipment, Section 4.3.1. Under the current standard restraint lanyards are required to include an energy absorber.28

Figure 13: The loader bucket in a raised position on 28 June 2012. The yellow marker post in front of the loader represents the height of the shaft gate.21

The consultants identified that the rigger’s fall arrest equipment (harness and lanyard) and the second mine worker’s lanyard would not have passed fit for purpose inspection if the equipment had been subjected to inspection in accordance with manufacturer’s user guides and guidelines published in Australian Standards (see Figure 18). 29

“Supervisors involved in the task planning did not document how the task was to be performed.”

Lanyard reeving method

The rigger’s fall arrest equipment lanyard was back hooked (choked) around a hole in the bucket and the Pensafe steel double action snap hook clipped back onto the lanyard rope (see Figure 19).

The method that the rigger used of back hooking the lanyard to the bucket was not recommended by the published guidelines in AS/NZS 1891.4:2009 figure 4.8 back hooking of lanyards (Figure 20). 32

Laterally extended anchorage line reviewed at simulation testing

The use of the lanyard by the two mine workers placed the lanyard in a lateral position.

Australian Standards have identified ‘safe use problems’ when anchorage lines are extended laterally.

The following is an extract taken from AS/NZS 1891.4.2009: 5.2.4:

Safe use problems are likely to arise if fall arrest devices are used in situations where the anchorage line is extended laterally from an anchorage point before reaching a point where the user is at risk of fall as illustrated in figure 5.3.’ and;

Unless specific advice is given by the manufacturer of the fall arrest device that the particular equipment can be safely used in this way, it shall not be so used.

Figure 17 Above: Remnant of the injured rigger’s fall arrest lanyard as found on the loader bucket. Note the remaining components of the failed lanyard have not been recovered from the base of the shaft.1

Simulations were conducted using the second mine worker’s lanyard back-hooked to the top of the bucket similar to how the rigger had back-hooked the lanyard to the bucket.

Observations from the simulation identified that the lanyard when extended laterally could not reach the front lip of the bucket. It was observed the lanyard could laterally reach to the side edge of the bucket.

It was observed that in the scenario using a 2-metre lanyard back-hooked around the top of the bucket and a person falling over the front lip of the bucket would result in the harness and upper body of the person striking the front edge of the bucket during the fall.

The angle of the rigger’s lanyard at the instant the lanyard failed is not known (see Figure 22).

Remedial actions

Following the incident, the mine took the following remedial actions:

- An accredited height safety equipment inspector inspected all fall arrest system equipment at the mine.

- Fall arrest equipment that did not pass inspection was removed and tagged out of service.

- The mine introduced an inspection program of all height safety equipment on a quarterly basis.

- The mine revised and formalised a management plan for height safety equipment.

- All new workers were inducted and given clear instructions that working at heights in anything other than a ‘certified man riding basket’ was not permitted.

- Mine worker induction documents were amended to prohibit operators from working out of a loader bucket and describe the height safety equipment inspection and testing process and coloured tag expiry system.

- Mine Rescue Officers were trained and accredited to inspect and maintain height safety equipment.

- All height safety equipment was required to be stored in the safety store and issued on a shift by shift basis. A trained and accredited Mines Rescue Officer was to inspect it when it was returned to the store at the end of the shift.

- Any defective equipment was taken out of service until it was inspected by an external accredited height safety equipment inspector during the next quarterly visit to site.

- New harnesses and lanyards came into the system only after they were inspected, tagged and marked with a unique identification and added to the equipment register.

- Every item in the height safety equipment register was inspected and certified as ‘fit for purpose’ on a quarterly basis.

- All height safety equipment in use was required to display the nominated colour tag to verify that it was ‘fit for use’.

- The mine communicated the incident to the workforce and provided information about the injured workers’ conditions and the impact on the mine’s operation.

- Safety meetings were held where a PowerPoint presentation was delivered to all workers and included the department’s Safety Alert (SA 12-03) Worker loses leg in fall.

- The Perilya Mine Health and Safety Committee members were included in the information meetings and two committee members were involved in the incident investigation team.

References

1. Working at Heights Association – Glossary of terms (issued 22/09/11) Fall-arrest System – An assembly of interconnected

components comprising a full body harness connected to an anchorage point or anchorage system either directly or by means of a lanyard or pole strap, and whose purpose is to arrest a fall in accordance with the principles and requirements of ASNZS 1891.4. (AS / NZS 1891.4 Clause 1.4.5).

22. Photograph by department investigator taken on 28 June 2012.

23. NSW Workcover Managing the Risk of Falls at Workplaces Code of Practice December 2011 – lanyard an assembly consisting of a line and components which will enable connection between a harness and an anchorage point and will absorb energy in the event of a fall.

24. As above.

25. As above.

26. As above.

27. Consultant’s reports dated 4 and 20 October 2012 and consultant’s report dated 25 June 2012.

28. Extract from consultant’s report dated 4 October 2012 – PPE inspection results report.

29. Consultant’s report dated 20 October 2012

30. Photograph by department investigator taken on 4 July 2012.

31. Photograph by department investigator taken on 28 June 2012.

32. AS/NZS 1891.4.2009 section 4.3.7 Back hooking

33. Photograph by department investigator taken on 28 June 2012.

Add Comment